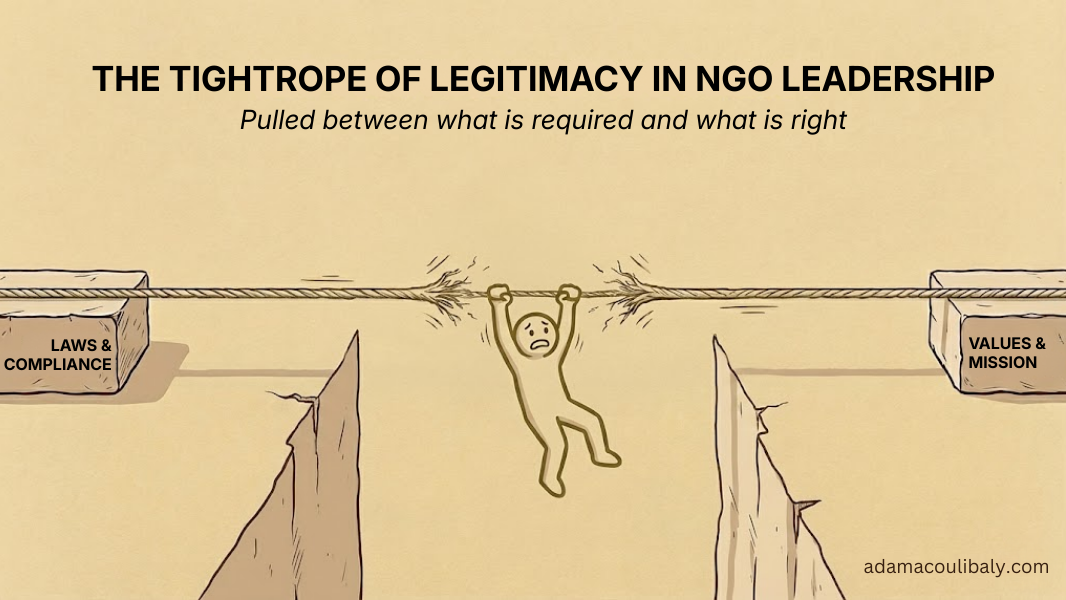

The Tightrope of Legitimacy in NGO Leadership

Pulled between what is required and what is right

PositiveMinds | Positive Stories | Edition 072

Illustrated by me (A. Coulibaly) with canva.com and Gemini by Google

There is a particular kind of silence that settles when every option feels wrong.

Not dramatic silence. Not the absence of noise. The quieter kind that arrives when you realise that whatever you decide next will protect something and compromise something else.

That night, the office was still. Two colleagues had been kidnapped. Negotiations were ongoing, stretched thin by long pauses that carried more weight than words. Outside, life continued, unaware of the calculations taking place behind closed doors.

On my desk were three stacks of paper.

They did not look extraordinary. No red flags. No urgent markings. Just documents waiting for their turn. Yet each one pulled in a different direction, and together they left no safe centre to stand on.

Only later did I understand that this was not simply a moment of crisis management. It was a moment of legitimacy being tested.

Legitimacy is not balance. It is sustained tension.

That night took place a few years ago in Goma, in the Eastern Democratic Republic of Congo. While the details belong to that context, the tension itself has followed me far beyond it.

That is what the tightrope represents for me. Not elegance, but endurance.

The first stack related to engagement with a non-state armed actor exercising de facto control over the area where we were implementing an emergency programme. The response focused on protection, with a strong emphasis on gender-based violence, in a context where sexual violence against women and girls was widely reported. The position communicated was explicit. Continued access was conditional. All GBV programming had to be suspended. Our presence could continue only if the work were limited to activities considered acceptable and non-threatening: water and food distribution, and basic education.

Access, in this case, came at the cost of independence and neutrality. Priorities were no longer shaped solely by needs, but by what those in control were willing to tolerate. Humanity called for presence, care, and response to lived harm. Remaining present, however, required stepping back from the very work that addressed that harm most directly.

Access can demand silence precisely where harm is loudest.

The second stack was correspondence with a donor. An allegation of fraud involving a partner had been reported. Transparency triggered a formal, process-driven response. Funding could be placed on hold unless a comprehensive audit was completed within a short timeframe. Accountability mattered. Assurance mattered. Gradually, attention shifted. Time and energy shifted from people to proof. Process began to crowd out action.

What protects the system can quietly constrain the work.

The third stack was an assessment of a nearby crisis. Families displaced, often repeatedly. Needs that were immediate and layered. Shelter that offered more than temporary cover. Water that was safe and close enough to access without risk. Food that sustained beyond the next distribution cycle. Dignity that could not be postponed. The recommendations were clear, grounded, and operational. The urgency was unmistakable. What was missing was not understanding, but space to act.

None of these stacks was unreasonable in itself. Together, they formed a standstill.

In that moment, leadership did not feel decisive or heroic. It felt suspended. Pulled between incompatible truths. Every option carried a moral cost. Every delay had a human consequence.

Those nights in Goma felt overwhelming at the time. With distance, they feel familiar.

Across the sector, this tension appears in many forms. In places where civic space is narrowing. Where organisations can be asked to leave with little notice. Where language, posture, and timing are constantly assessed. Where leaders weigh, day after day, whether to exercise their mandate openly or to lower visibility to protect people.

In such contexts, voice becomes complicated.

Having a voice is not the same as using it loudly. There are moments when speaking clearly is essential. There are also moments when restraint is the more responsible choice. Not because the issue matters less, but because the cost of noise may be borne by others.

For many, this understanding comes slowly, especially for those who are naturally vocal. Silence, in certain circumstances, can carry more meaning than any statement.

We are required to comply with increasingly complex laws and regulations. To satisfy donor requirements shaped by risk aversion and scrutiny. To uphold the duty of care to staff. And, at the same time, to remain faithful to values, mission, and the communities we exist to serve.

Neither access negotiations nor accountability requirements stop the work outright. Together, however, they narrow the space in which the work can breathe. And it is almost always the needs on the ground that absorb the impact.

Needs do not pause because negotiations are delicate. Displacement does not slow because audits are underway. Communities do not experience our constraints as context. They experience them as delay.

We wrestle with process. They live with consequences.

We debate thresholds and tolerances. They absorb the impact.

We manage risk. They carry the cost.

Over time, our sector has built layers of protection around itself. Each layer exists for a reason. Each responds to real risk. As they accumulate, what protects institutions can quietly constrain purpose.

For those of us in senior leadership roles, this tension is deeply personal. Leadership is often associated with confidence and clarity. In practice, it is frequently uncertainty carried quietly so others can keep moving. It is absorbing doubt, fear, and fatigue without passing them further down the line.

Leadership today is less about control, and more about containment.

We are not superheroes. We do not have infinite resilience or perfect moral clarity. Pretending otherwise does not strengthen leadership. It narrows the space for honest judgment and shared responsibility.

And yet, stepping away is not an option.

For people driven by purpose, the work does not resolve neatly. Issues continue to surface. Inequality, injustice, and poverty do not recede simply because effort is sustained. This continuity is both the reason many stay and the weight they carry.

The causes we work for are far larger than our organisations, our titles, or our discomfort. The pressures we navigate are real, but they are not comparable to what communities endure every day. We struggle with systems. They live with consequences that shape their safety, dignity, and survival.

Holding that perspective does not remove the strain. It gives it proportion.

Across humanitarian and development organisations, leaders are walking the same tightrope. Pulled between what is required and what is right. Between compliance and conscience. Between staying present and staying principled.

The question is not whether the rope is under strain. It is. The question is how we respond to that strain.

Not by shouting louder, but by choosing when to speak and when restraint serves better.

Not by abandoning principles, but by holding them with humility.

Not by adding more processes, but by asking which safeguards truly protect people and which primarily protect institutions.

As I reflect on the path that brought me here, I think of the younger professional I once was. Aspiring to a role like the one I hold today. Global Programmes Director in a global and respected organisation like Oxfam. It represented reach, influence, and the potential to contribute at scale. I remain deeply grateful for that trust.

What I did not fully see then is what comes with it.

The weight of decisions whose effects ripple far beyond their point of origin.

The solitude of responsibility that cannot always be shared.

The discipline of restraint, when having a voice does not always mean using it.

If I could speak to my younger self, I would not tell him to aim lower. I would tell him to aim deeper. To expect uncertainty. To build endurance. To remember that presence matters more than performance.

And I would remind him of this. The position is never the point. The people are. The communities we serve will always carry more than we do. Our discomfort, our constraints, our fatigue, real as they are, do not absolve us of responsibility. They ask us to act with clarity rather than ego, with courage rather than volume.

I return to that night sometimes. To Goma, in the Eastern Democratic Republic of Congo. A place shaped by more than three decades of crisis, where instability is not an episode but a condition. What felt overwhelming to me in that moment was, for the people around us, part of a much longer continuum. That perspective stays with me. It reminds me why staying present matters, even when the space to act feels impossibly narrow.

The work is not to walk the rope more elegantly, but to strengthen what holds us together.

Perhaps that is where legitimacy truly lives.

#HumanitarianLeadership #GlobalDevelopment #NGOLeadership #HumanitarianPrinciples #CivicSpace