The Price of Proof

How compliance quietly consumes impact

PositiveMinds | Positive Stories | Edition 071

Illustrated by me (A. Coulibaly) with canva.com and Gemini by Google

Across the humanitarian and development sector, the demand to demonstrate impact has never been higher. Donors face legitimate pressure from taxpayers and parliaments to account for every cent spent. Organisations operate in an environment shaped by past failures, public scrutiny, and genuine concern for effectiveness. Accountability matters. Evidence matters. Proof matters.

Yet the question confronting the sector today is not whether we should prove impact, but how much proof is enough, and at what cost.

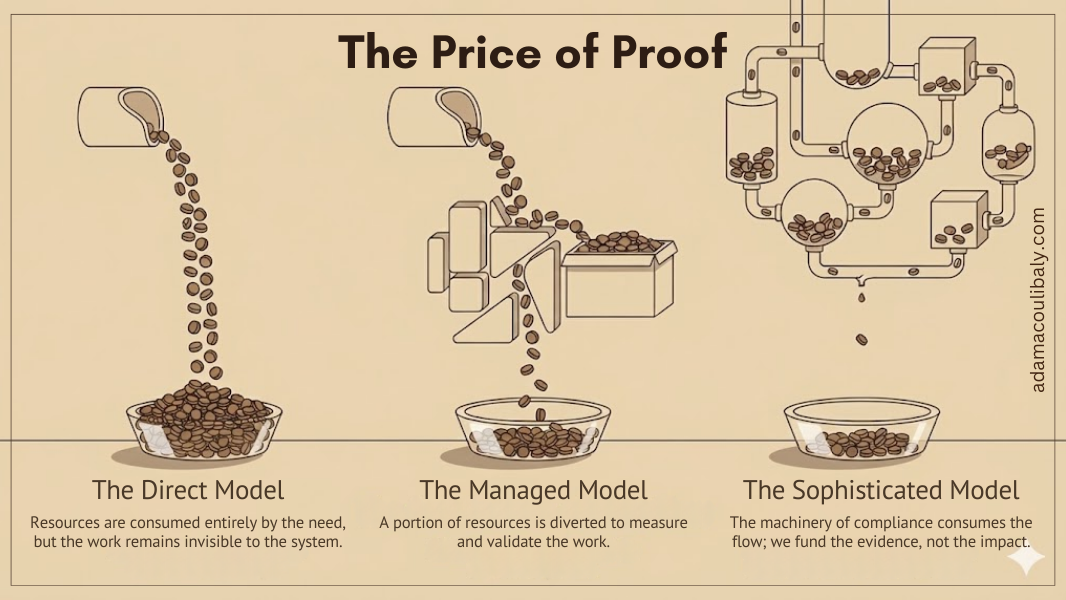

Over time, accountability systems have evolved. Early models prioritised direct delivery and proximity to need, often with limited formal reporting. As funding grew and expectations increased, systems emerged to measure, validate, and standardise results. More recently, these systems have become increasingly sophisticated, layered with compliance checks, verification mechanisms, and reporting architectures designed to reduce risk and ensure control.

Each step was introduced with good intentions. But together, they have created a quiet paradox: the machinery designed to protect impact is increasingly consuming it.

When evidence displaces judgement

A growing body of research highlights the rising burden of reporting and compliance. The State of the Humanitarian System reports by ALNAP consistently point to performance constraints driven by complexity, fragmented accountability, and incentives that prioritise process over learning (ALNAP, 2022). Similarly, the Grand Bargain explicitly committed donors and agencies to simplify and harmonise reporting, recognising the high transaction costs imposed on delivery chains, particularly on local partners (ICVA, 2022).

The result is not only inefficiency. It is abstraction.

As accountability travels upward through systems, it becomes increasingly removed from lived realities. Data are aggregated, standardised, and formatted to meet institutional needs. Context, nuance, and judgment are gradually filtered out. Impact is proven, but often in ways that flatten experience rather than illuminate it.

This matters in a moment of humanitarian reset. When crises are more frequent, protracted, and complex, rigid compliance systems slow response, reduce adaptability, and constrain local leadership. They also reinforce long-standing power imbalances: evidence is valued most when it is produced, interpreted, and validated far from the communities it describes.

This is not about intent. It is about structures.

Good practice already exists.

The picture is not uniformly bleak. Across the sector, there are credible efforts to rebalance accountability and impact.

Some pooled funds and donors have simplified reporting requirements for smaller grants or trusted partners. Others have piloted outcome-oriented reporting that focuses on decision-relevant information rather than exhaustive indicator frameworks. Research from the Overseas Development Institute (ODI) on adaptive management and evidence use shows that rigorous learning is strongest when evidence is closely linked to real-time decisions, rather than expanded reporting obligations (ODI, 2019).

Trust-based approaches demonstrate that proportional oversight can coexist with rigour. These examples matter because they show that the choice is not between accountability and effectiveness. It is between different ways of practising accountability.

Three proposals to rebalance proof and purpose

If the sector is serious about localisation, decolonisation, and the humanitarian reset, it must move beyond critique and make practical shifts. Three are particularly urgent.

First, anchor evidence requirements in decisions, not templates.

Every data request should be linked to a clear decision it is meant to inform. If information does not influence funding, strategy, or operational choices, it should not be collected. This “minimum viable evidence” approach reduces burden while sharpening judgment.

Second, make accountability proportionate and shared.

Risk, funding size, and context should determine the depth of reporting, not institutional habit. Where possible, a single evidence set should serve multiple accountability needs, rather than requiring partners to repackage the same information repeatedly for different audiences.

Third, use AI to reduce compliance load, not increase surveillance.

Artificial intelligence can be used responsibly to synthesise reports, translate local narratives, identify patterns across programmes, and surface insights from existing data. If treated as an enabling capability rather than a control tool, AI can shift human effort away from formatting and verification and towards learning, reflection, and action.

Choosing impact over accumulation

The humanitarian and development sector does not suffer from a lack of evidence. It suffers from excessive accumulation without sufficient sense-making.

Proof should support impact, not replace it. Accountability should enable trust, not compensate for its absence. Evidence should travel to where decisions are made, not accumulate where lives are lived.

The price of proof is not only financial. It is measured in time, attention, and distance from the people the sector exists to serve. Reducing that price is not about lowering standards. It is about restoring purpose.

#HumanitarianReset #AidEffectiveness #Localisation #Accountability #Impact #AIforGood