The Work Beneath the Work

On power, posture, and what quietly shapes humanitarian action

PositiveMinds | Positive Stories | Edition 073

Illustrated by me (A. Coulibaly) with canva.com and Gemini by Google

In the humanitarian sector, the visible machinery of response captures our attention: logistics, fundraising appeals, and metrics of success. This work is essential. It saves lives, fills logframes, and accounts for the resources entrusted to us.

But as the world becomes more multipolar and vocal, the shape of our role must change. This is not about dismissing the sector. There is, and will always be, a vital space for international NGOs. We bring solidarity, technical expertise, and the ability to bridge divides.

To remain relevant, however, we must engage with another dimension of our practice.

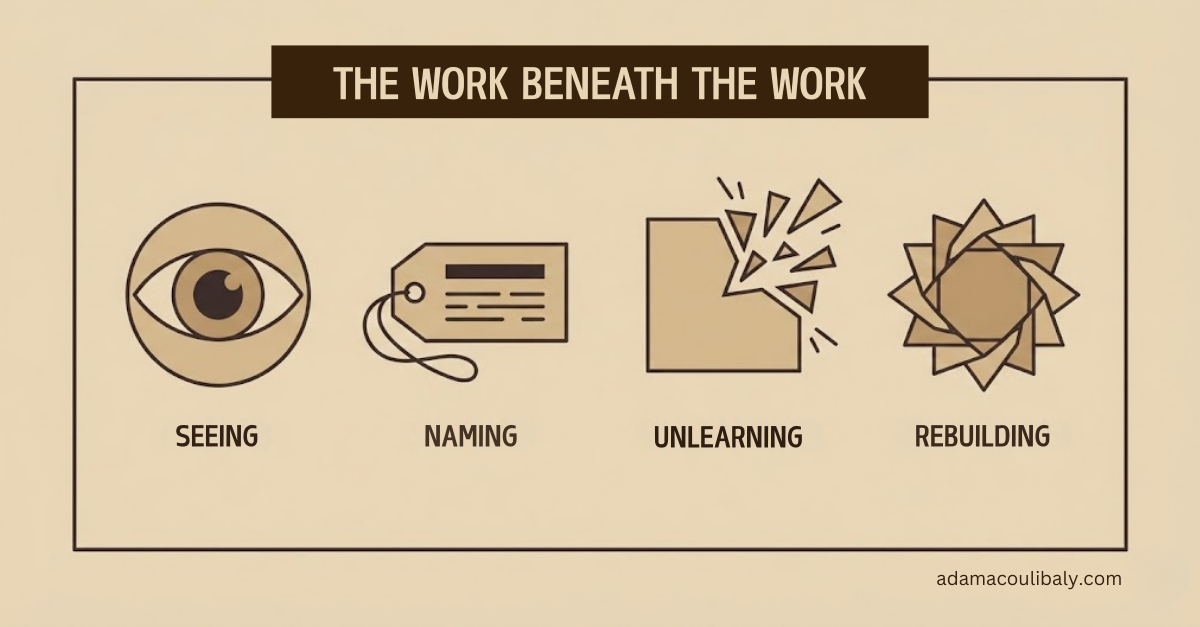

I call this "the work beneath the work."

It is the act of examining the foundations of the system we inhabit to ensure they fit the future. It requires us to look beyond the technical "toolbox" of aid and commit to a cycle of professional evolution. These are not steps on a linear ladder, but intersecting layers of practice we must return to again and again.

Seeing (Epistemic Vantage)

The most effective systems are often the ones we stop noticing; they become the "natural order of things." For decades, we have relied on standard tools—needs assessments, capacity statements, logframes, Theory of Change—assuming they were neutral. Yet, as we evolve, we realise these tools can sometimes impose an external order rather than support the growth of indigenous systems.

The challenge for any leader navigating this space is to avoid simply repeating these patterns. Large organisations can be like the Titanic: steady, powerful, but slow to turn. To navigate these waters, we must approach the sector with a "clean sheet," bringing fresh eyes to challenge our assumptions.

To see clearly, we must broaden our perspective. We must look at the decision-making table and ask: Who holds the budget? Whose knowledge is viewed as "expertise" and whose is seen as "anecdote"?

"Before we can change the system, we must learn to see it. Seeing means making power visible: who decides, who defines, who benefits, and who speaks for whom."

Naming (Linguistic Agency)

Once we perceive these dynamics, we need the precise vocabulary to describe them. Language is rarely neutral; the words we choose shape the reality we create.

Our sector has long relied on terms such as "beneficiaries," "empowerment," and "capacity building." These terms are often well-intentioned, but they can inadvertently mask power imbalances. We often use deficit-based language—describing communities by what they lack—to explain our presence.

We strengthen our impact by reclaiming our linguistic agency. Instead of defining partners by their needs, we must define them by their assets and rights. Naming concepts like "colonial legacies" or "structural racism" is not about assigning blame. It is about turning a vague sense of institutional unease into concrete challenges we can solve.

"Language is power, and naming is the first act of reclaiming it. Naming turns discomfort into analysis and silence into vocabulary."

Unlearning (Destabilising Knowledge)

This is perhaps the hardest layer of practice. Unlearning is more difficult than learning because it requires us to reconsider the methods that defined our success for decades.

A critical distinction is between localisation and decolonisation. These concepts are frequently conflated. Localisation is often treated as an implementation mode—a way to improve "delivery" while keeping the strategic string attached. Decolonisation is about autonomy; it is about cutting that string.

Institutions seek stability, so shifting our operating models feels risky. It forces us to acknowledge that the "expertise" we honed may need to shift from leading to supporting local action. We are moving from an era of direct implementation to one of facilitation.

"Unlearning is harder than learning because we must let go of what once made us feel competent. Institutions resist unlearning because it threatens status, expertise and identity."

Rebuilding (Consent & Plurality)

Decolonisation is not about subtraction; it is about reconstruction.

It is not about dismantling the sector, but about ensuring our future structure is built by new architects, using new materials. This rebuilding invites us to anchor our work in three principles: Consent (moving beyond consultation), Plurality (embracing multiple paths to development), and Tangible Power Transfer.

This raises a question about solidarity. Solidarity is not charity; it is an investment in our collective future. A crisis anywhere affects us all.

But this rebuilding brings friction. We increasingly face donor conditions that challenge our humanitarian principles. The difficult choice we often face is between compliance to secure funding and the principled refusal necessary to maintain our integrity. The goal is to evolve without losing the soul of our mission.

"The point is not to destroy the house, but to rebuild it with new architects, materials and consent. Decolonisation is not subtraction, it is reconstruction."

The work of rebuilding is never finished. It is not a checklist we complete; it is a continuous practice.

The future of our sector is not a paved highway waiting for us; it is a path we must construct as we walk it. It requires constant vigilance to ensure our adaptation keeps pace with the world around us, and a commitment to collectively author our future.

#DecoloniseAid #ShiftThePower #HumanitarianAction #AidReimagined #Leadership #Localisation