Decision-making in a permacrisis context when rationality reaches its limits.

Positive Minds | Positive Stories | Edition 032

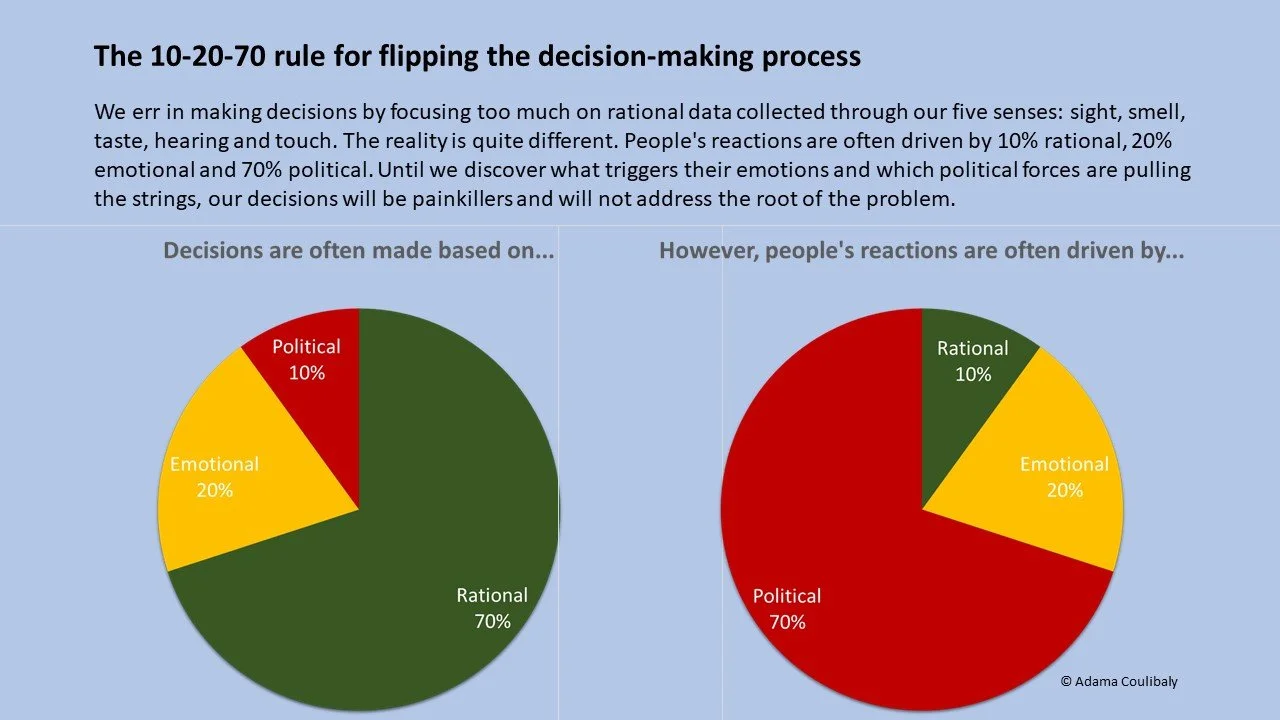

Rational decision-making frameworks have limits in permacrisis —an extended period of instability and insecurity, especially one resulting from a series of catastrophic events. Leaders and managers do not find adequate answers in organisational blueprints. They should be able to experiment with alternative decision-making frameworks, relying less on rational data and more on people's emotions and the political forces at stake.

2022 was a cruel year for the populations of eastern DRC. It has been so for almost three decades. And 2023 does not look good. Hundreds of people are slaughtered, looted, abused and often raped, especially women and girls. Attacks on civilians, including in IDP camps, are increasing. Thousands of people are fleeing their homes, adding to the millions displaced or refugees by years of conflict.

The data is shocking. More than 27 million Congolese face severe and acute food insecurity (about 1 in 4 people). Nearly 5.5 million are internally displaced, some forced to move several times in a pendulum movement. At least 500,000 refugees and asylum seekers from neighbouring countries are hosted in the DRC [Cf. OCHA].

Such figures should provoke a surge of international solidarity to help the Congolese people, innocent and powerless victims of the wars and conflicts ravaging their country. This is not the case. As a sub-regional crisis, the DRC ranks first in the 2022 index of underfunded crises. In 2021, the humanitarian response plan was the least funded since 2017, with just 39% of the USD 1.98 billion needed [Cf. OCHA]. 2023 will be no different.

With the escalation of conflicts, most notably between the armed group M23 and the DRC armed forces (FARDC), population movements are increasing, and so are humanitarian needs, while funding is stagnating or decreasing. Humanitarian and development leaders like me are forced to make difficult, often reluctant, strategic and operational decisions concerning their staff and partners, and most importantly, those in need: the humanitarian aid clients.

In this permacrisis context, leaders are helpless and sometimes powerless. They and their teams struggle to establish cause-and-effect relationships between events around them. But given the scale, impact and velocity of crises, the conventional decision-making tools at their disposal show their limits. The word of the gospel today is the word of the devil tomorrow. What healed yesterday hurts today. What is revered one day is rejected with the utmost energy the next. The examples are legion...

A rapid humanitarian needs assessment, conducted the day before to develop a concept note for your major donor, becomes useless when thousands of displaced people return home the following day, hungry, thirsty and at risk.

A road deemed safe at 7 am suddenly becomes perilous at 8 am because rival armed groups are fighting or disgruntled youths are barricading roads and burning tyres in protest of growing insecurity.

A youth group in one community threatening to ban all international NGOs unless they meet their demands, including implementing more cash-for-work programmes and recruiting at least 60% of staff locally, among other requests.

A decision to suspend the issuing of visas by DRC embassies and consulates to the staff of all INGOs travelling to the four eastern provinces most affected by the crises; amidst rumours of enemy infiltration of the latter.

You develop a rapid response plan to provide humanitarian assistance to an influx of 10,000 displaced people, but as fighting intensifies, their numbers increase tenfold in less than a month, thereby making your strategy at best useless, at worst harmful.

The list is as long as your arm...

Each of these scenarios makes rational decision-making complex. And when they occur concurrently, as they often do, rational decision-making becomes irrelevant and ineffective.

So what do you do when rational tools, including organisational policies, procedures and SOPs, reach their limits? Challenge the conventional wisdom of decision-making.

The conventional wisdom of decision-making or the 70-20-10 Framework

From the first year of primary school, until you get your Bachelor's, Master's or PhD, you are taught that 1+1 = 2 and that rational thinking, facts and evidence should always guide your approach to problem-solving. Your teachers and employers leave you little room to use divergent thinking based on emotions and even less on politics. You are trapped in the 70-20-10 decision framework, the ingredients of which are:

70% Rational: your decisions are guided by at least 70% rational, i.e. by the data you collect using your five senses: sight, hearing, smell, taste and touch. As a result, most people and organisations spend considerable time, resources and energy collecting such (rational) data to support their decisions.

20% Emotional: emotions cannot be seen, heard, smelled, tasted or touched. Emotions are felt. Conventional wisdom teaches us not to use our emotions in decision-making. However, as human beings, we cannot help but use emotion to inform our decisions.

10% Politics: although organisational politics often influence our decisions, we rarely use Politics with a capital P to inform our decisions, even though we know that Politics is all around us. If you don't do politics, politics will do you.

This 70-20-10 framework works well in a stable environment with clear and predictable cause-and-effect relationships. It does not work in a permacrisis environment such as the eastern DRC.

So, what do we do? Quite simple. Turn the conventional framework upside down and make it a 10-20-70.

A new decision framework for permacrisis contexts or 10-20-70 Framework

Conventional decision-making wisdom favours scenario planning or 'what-if' scenarios. However, in a permacrisis context, scenarios are unpredictable and constantly shifting. The rational decision-making framework leads to over-analysing risk to the point of decision paralysis. While you incubate your scenarios, your environment has changed so much that they become outdated when they mature.

In a permacrisis situation, organisational policies, procedures and SOPs —however well thought out and developed— can quickly become barriers rather than enablers. Why? Because they are shaped by past experiences and not inspired by future prospects.

In such a context, you must flip the conventional 70-20-10 framework into a 10-20-70 because people's reactions are often dictated by 10% rational, 20% emotional and 70% political. And until we know what drives their emotions and what political forces are at stake, our decisions are painkillers that don't address the root cause of the problem.

As one of my mentors once said;

"As a leader, you should understand that things are not black or white. Things are 5% black, 5% white and 90% grey. Organisational policies, procedures and SOPs are developed to address the 5% black and the 5% white, barely 10%. Your role is to bring light to the 90% of grey".

I would add the "90% grey = 20% emotion + 70% politics", hence the need to reverse our decision-making process in a permacrisis context. I have experimented with this new way of thinking over the last 12 months. It works as long as your line manager trusts you and gives you space and authority, and your organisation is agile and adaptable enough to embrace new ways of doing things. I feel fortunate to have both.

What decision-making framework do you use in a permacrisis context? Leave your suggestions in the comments.